The LORD God commanded the man, “You are free to eat from any tree in the garden; but you must not eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, for when you eat of it you will surely die.” (Genesis 2.16-17)

Trees Talk

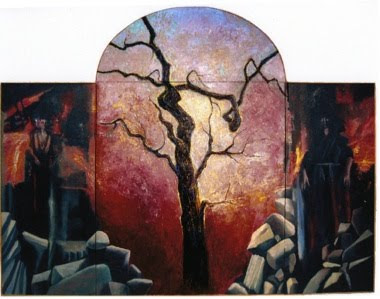

Trees talk in the Bible—not audibly, but they routinely tell us about ourselves. They reveal how easily we’re tempted by forbidden fruit. They describe our character. They catch us riding too high for our own good. They invite us into their branches when our only hope of seeing Jesus depends on being lifted above the crowd. They attest to our faith. They predict what happens when we bear bitter fruit and explain how we’re knitted together as one organism. They appear in visions to promise healing. Trees have a lot to say in Scripture and we’ll spend the next few posts listening to them. In this post, we attend to the first talking tree—indubitably the Bible’s best-known tree, the one at the center of our drama, the reason why other lessons from trees are necessary.

The Tree of Knowledge

It stands as the centerpiece of Eden: the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil. “Here’s how this works,” God tells Adam and Eve. “Do what you want and you’ll do just fine. You’ll be happy. I’ll be happy. The garden will thrive. We can go on like this forever.” But there’s a catch. (See? It’s gone like that from the beginning. There’s always a catch.) “Just keep away from the Knowledge Tree. I know it’s one-of-a-kind. I know I’ve put it in the middle of everything. I know its fruit looks delicious. But you have to ignore it. Take a bite of its fruit and you will surely die.”

For those who don’t like God too much—the ones who can’t reconcile Who He says He is with His up-front cause-and-effect conditions and judgment—this seems like the first of many examples where He stacks the odds against us. Why put the tree there at all? If we couldn’t have it, why tempt us with it? Why tell us to stay away, subtly planting the idea we should try it to see what happens? And what does He use to leverage His edict? Death—a concept as alien to Adam and Eve as Hell (a.k.a. “The Second Death”) is to most of their offspring. Why, why, why? You don’t have to be disenchanted with God’s methodology to ask these questions. If Eden is supposed to be perfect, it’s fair to question why He introduces a way to potentially ruin it. The answer isn’t buried in our nature, the Tree’s nature, or even nature itself. It’s hidden in plain sight, in the context surrounding all those natures. And it’s pretty basic.

A New Faculty

Outside of God Himself (Who is absolutely perfect), perfection is a conditional quality that can only exist opposite imperfection. In fact, all of creation is conditional. We know, for instance, what light is by what it is not and vice-versa for darkness. We distinguish the elements—land, water, and air—more concretely as not like each other than what they actually are. Organizing the world by opposites is instinctive. It’s inherited from our Creator Who, from His first appearance in Genesis, reveals Himself as a categorical Thinker. Without potential imperfection, sorrow, and death, there is no potential for perfection, joy, and eternal life. So the Knowledge Tree’s potential destruction of perfection isn’t made for that eventuality. Actually, it’s designed to establish perfection, a world of beauty and emotion sustained by instinctive innocence. As Adam and Eve soon learn, however, the slightest taste of knowledge trumps the full flavor of instinct every time. Before they disobey and bite into the Knowledge Tree’s fruit, they sense things rather than know them. They experience the world objectively, without any fear or caution. Once they know, however, they have a new faculty. They can discern good from evil, right from wrong. The author of Genesis says, “The eyes of them both were opened and they knew.” (Genesis 3.7; KJV) The serpent promises they won’t just be surrogates for God, they’ll be like Him in every way and he doesn’t mislead them. God reserves knowledge for Himself but—true to form—His obsession with polarity compels Him to make it solely His by putting it at risk.

A Ruinous Legacy

We were never meant to discern good from evil. It was never God’s intention to burden us with judgment of any kind. His only purpose for creating us in His image and breathing His life into us was to bring Him pleasure by reflecting His goodness in His world. Had Adam and Eve resisted the Knowledge Tree’s temptation, all we see and know about this place and one another would be good. I couldn’t question your making. You couldn’t doubt mine. Each of us would be uniquely shaped, yet we’d intuitively realize God’s reflection equalizes us. Would we still make mistakes? Yes. Innocence doesn’t ensure infallibility. Would we be susceptible to temptation? Yes. Evil’s presence would remain for goodness’s sake. But inability to discern good from evil would relieve our need to apply what we took from the Knowledge Tree to what we experience in the world. Though we would be no less human, weaknesses and vanities that thwart our flesh wouldn’t be perceptible to us. Instead of being victims of sin, we would be vessels of grace—which is what we truly are.

Last week’s observance of John Lennon’s 70th birthday flooded us with replays of “Imagine”—a song I find lamentable for its agnostic premise. Pretending we’re not accountable for good and evil, right and wrong won’t lift the burden of Adam and Eve’s recklessness. If only it were as easy as imagining the tree incident never occurred! But it did and, seen literally or metaphorically, its truth holds. Biting into forbidden fruit taught us too much—just not enough by yielding not one grain of God’s wisdom. The Knowledge Tree reminds us the faculty we use to condemn others was stolen and consumed under Evil’s influence. It’s a fallacy to think sinfully gained knowledge can assess sin. It’s even more foolish to presume knowing what God knows with none of His wisdom qualifies us to judge in His name. That’s why confessing we can’t possibly understand what we know reconciles us to God. It’s not our knowledge that pleases Him, but our desire to be what He created us to be, mirrors of His goodness and vessels of His grace.

(Portions of this post first appeared in Straight-Friendly: The Gay Believer’s Life in Christ in a slightly modified form.)

We stole and consumed the knowledge of good and evil under Evil’s influence. It’s a burden we were never meant to carry, a faculty we’re not sufficiently equipped to use.